Weston Middle School

Technology/EngineeringCourse Materials

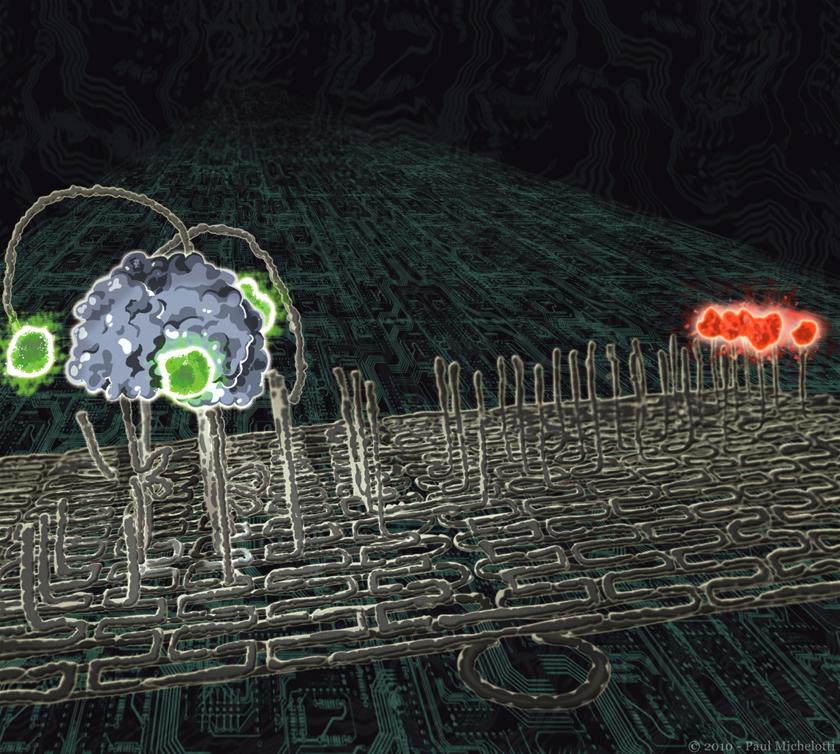

The molecular nano-bot, dubbed a "spider", walks along a track built upon a DNA origami scaffold (Source: Paul Michelotti)

US scientists have created a molecular robot made out of DNA that walks like a spider along a track made out of the chemical code for life.

The achievement, reported in the journal Nature, is a further step in nanoscale experiments that, one day, may lead to robot armies to clean arteries and fix damaged tissues.

The robot is just four nanometres, four billionths of a metre, in diameter.

Milan Stojanovic of New York's Columbia University , who led the venture, likens the nanobot to "a four-legged spider".

The beast moves along a track comprising stitched-together strands of DNA that is essentially a pre-programmed course, in the same way that industrial robots move along an assembly line.

The track exploits one of the basic characteristics of DNA. A double-helix molecule, DNA comprises four chemicals which pair in rungs.

By "unzipping" the DNA, one is left with one side of the strand whose rungs can then be paired up with matching rungs.In other words, the track can be used rather like the teeth in a clockwork mechanism. A cog can move around the teeth, provided it meshes with them.

By using strands that correspond to sequences in the track, the robot can be made to walk, turn left or right as it is biochemically attracted to the next matching stretch.The spider's "body" is a common protein called streptavidin.

Attached to it are three "legs" of single-strand enzymatic DNA, which binds to, and then cuts, a particular sequence of DNA. The fourth leg is a strand that anchors the spider to the starting point.Staying on track

"After the robot is released from its start site by a trigger strand, it follows the track by binding to and then cutting the DNA strands," says Stojanovic.

Once the strand is cut, the leg starts reaching for the next matching stretch of DNA in the track. In this way, the spider is guided down the path set by the researchers.

Eventually, the robot encounters a patch of DNA to which it can bind but cannot cut. At that point, it is immobilised.

Watching the spider strut its stuff was in itself a technical challenge.

The researchers used techniques called atomic force microscopy and single-molecule fluorescence microscopy which showed the molecular robots following four different paths.

Molecular robots have drawn huge interest because of the allure of programming them to sense their environment and react to it. For instance, they could note disease markers on a cell surface, decide that the cell is cancerous and needs to be destroyed and then deliver a compound to kill it. Other DNA walkers have been developed in the past, but they have never ventured more than a few steps, says Dr Hao Yan, a professor at Arizona State University."This one can walk about to about 100 nanometers. That's roughly 50 steps."The next step is how to make the spider walk faster and how to make it more programmable, so that it can follow many commands on the track and make more decisions, says Yan.

Nano-machines

In a separate study reported in Nature, Nadrian Seeman and colleagues

from New York University said they had enabled a nano-scale "assembly

line". DNA walkers moved past three kinds of DNA machines that handed

them a cargo of gold nano-particles, which are clutched with three "hands".

"This is the first time that systems of nano-machines, rather than

individual devices have been used to perform operations, constituting

a crucial advance in the evolution of DNA technology," says Lloyd

Smith, a chemist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, in a commentary

also published by Nature.

Links